Thomas Hill - The author of the first beekeeping manual in England

Thomas Hill (c.1528-c.1574) wrote the first beekeeping handbook in English as well as a variety of 'scientific' manuals, almanacs, and gardening manuals.

Name: Thomas Hill

Born: c.1528

Died: c.1574

Location: England

Era: Early Modern

Bee link: Wrote the first handbook published in England on Beekeeping

Those of you who have been reading Honeybee Histories for a while, will know that I run an occasional series of essays about the first beekeeping handbook published in England. This handbook was by Thomas Hill, although a large bulk of the contents was little more than a translation of a similar book by Georg Pictorius. Hill was something of a freelance writer in Elizabethan England, and his skill was in compiling various sources together into a meaningful and understandable form. In this profile essay we dive deeper into the man himself and what historians have said about him since.

Thomas Hill was born in or around 1528. Little is known of his life. In 1568, Hill himself, suggested that he was a ‘Londoner’ (declared by him in the front matter of his treatise on bees) and he claimed that he had been ‘rudely taught, amongst the smiths at Vulcans forge’ rather than having ‘tasted of the learned Lake’ (in his conclusion to book two of his Profitable Art of Gardening). John Considine dismisses this claim, noting that even if Hill had had a poor education as he claimed, he had nonetheless become a good translator and had a keen knowledge of both Latin and Italian.

In 1944, Francis R. Johnson called Hill ‘an Elizabethan Huxley’ suggesting that he could be viewed as a sixteenth-century predecessor of the Victorian Thomas Henry Huxley. Huxley (1825-95) was an early advocate of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution; he was a self-taught biologist, having gained very little formal schooling and yet in the nineteenth century he became an authority on comparative anatomy. Huxley not only spoke to his peers about his findings, but also to the public in the form of lectures and articles. For Johnson, Thomas Hill did much the same in the sixteenth-century. Johnson suggests that Hill was ‘the active leader in expounding the mysteries of science in simple terms for unlearned laymen’. This is certainly not an unfair representation, although admittedly Hill worked on a much smaller scale than Huxley and there is little evidence that he was as learned as him. Hill spent his career writing and translating scientific handbooks designed for the London middle class. However, Hill was not necessarily an expert in all of these fields, if even any of them.

Publications

In terms of publications, Hill began with a translation from Latin, of a Physiognomy text. That probably requires some explanation as Physiognomy is now a very much redundant scientific concept. Essentially, physiognomy means:

“a work assessing a person’s character or personality from his or her outer appearance, especially from the face. From the Greek physis meaning ‘nature’ and gnomon meaning ‘judge’ or ‘interpreter’”.

In other words, the study was about being able to identify aspects of a person just by looking at their appearance, especially their face.

In 1559, Hill continued with his writings, by having published a compilation on the interpretation of dreams, and then in 1560 he produced the first in a series of almanacs (one of the first to do so in English). Later in his life, Hill would again publish on dreams, but also on phenomena such as comets, rainbows and earthquakes, on conjuring tricks and practical jokes, and left unpublished on medicine, astrology, and mathematics. He would also write about gardening, which is where the handbook on honeybees comes into the picture (I shall come to that in a moment).

The array of topics is extremely diverse and yet each of Hill’s publications hold one thing in common; they were each designed for the ordinary person to consume and understand. Hill, it would seem, prided himself on producing good quality translations that he believed the ordinary person would find interesting and useful.

Books on Gardening

It is Thomas Hill’s involvement in the field of husbandry that interests us particularly here. Hill first published on the subject of gardening and husbandry in 1558/1560 in his A Most Brief and Pleasant Treatise Teaching how to dress, sow and set a garden. This was the very first English publication on that subject, and it proved popular. In 1568, Hill expanded this treatise as The Profitable Art of Gardening, including an annexed treatise on beekeeping.

This was not his last word on the subject. Although Hill died in 1576, leaving various manuscripts incomplete and unpublished, his friends had published in 1577 a second manual on gardening that Hill had been working on. This was published under the pseudonym Didymus Mountaine and was called The Gardeners Labyrinth.

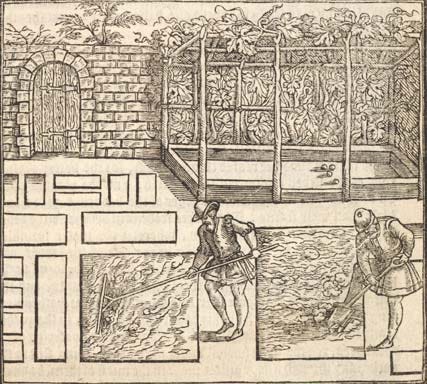

The woodcut of Thomas Hill

Usefully Hill had a woodcut made of him, so we have an idea of what he looked like. This woodcut appeared in several of his publications, including his treatise on bees. Johnson argues that the image confirms that Thomas Hill’s father was a ‘less well-to-do member’ of a London guild and that in the woodcut Hill is confirmed as a young citizen of London by his wearing of an unornamented flat cap (the fashion among the young citizens of London in the mid-sixteenth-century).

If Johnson’s assessment of Hill is correct, then it would appear that he was a man of modest means, who made a respectable amount of money through his publications, but never enough to be far from impoverished. Hill sold his manuscripts to various publishers and, it would seem, supplemented his income by working also as a press-corrector and scrivener. Essentially, Hill discovered a market untested before him. No one else had thought of publishing good quality manuals on husbandry for middle class audiences, and therefore Hill became ‘eminent’ in his field.

That role was not one in which original works were to be produced. Thomas Hill was essentially an early writer for the popular market, by selecting from learned men’s works and bringing them to a wider, often less-learned, audience. As Johnson wrote in 1944:

‘He contributed no original ideas, nor was he an expert in the subjects with which he dealt.’

At the time this did not really matter. Hill ensured that his publications were of a high quality both in terms of their printing and in terms of their lucidity and clarity. Many translations and compilations in the sixteenth-century were of poor quality, especially as they were not expected to make a great deal of money. Hill prized himself as better than that and made sure that what he published proved useful, easy to use, and inexpensive to buy.

Further Reading

John Considine, ‘Hill, Thomas (c.1528-c.1574)’, ODNB (2004) [doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/13303 ].

Francis R. Johnson, ‘Thomas Hill: An Elizanethan Huxley’, Huntington Library Quarterly, 7:4 (1944), pp. 329-351 [http://www.jstor.org/stable/3815736].

Hello Thomas—thank you very much for your detailed writing of apiary history. I’m having to sell some historic bee book treasures (eliminated fed job—Aaargh).

ABC and XYZ of BEE CULTURE, The A.I. Root Bee Library, 1975

Beekeeping, Boy Scouts of America, 1957

A Book of Bees, Sue Hubbell, 1988.

Are you interested? I am in Sacramento if you are close by?