Four Facts about the History of Bees

As an expansion of the World Bee Day series of tweets, this essay focuses on the Euglossini Bee, Trigona Prisca, Ancient Egypt, and the Red-Tailed Bumblebee.

This week Honeybee Histories presents four short facts about the history of bees. These were originally sent out as tweets in 2024 for World Bee Day. In this essay (as per previous editions of this series) we begin with a video montage of these fascinating facts and then dive deeper into the subject.

With the decline of Twitter, I won’t be doing 24 tweets for World Bee Day this year, but I do plan to continue these short fact pieces in a different form. I’m still working on ideas for that but in the meantime, there are still a few more of these from 2024 to work through this year.

As per usual, let me know what you think of these facts in the comments and if you have any of your own, please feel free to share them.

Fact #1: The Euglossini (Orchid) Bee

The Euglossini bee was the focus of my 2024 #WorldBeeDay essay. It’s a gorgeous bee, with a patched green colour and large bulging eyes. The fact that Charles Darwin focused on it to understand the relationship to the Bee Orchid (Ophyrys Apifera) is perhaps its most famous moment and most modern studies focus also on this symbiosis as well. But is this really an example of symbiosis or is it more that the orchid is simply taking advantage of the bee?

The attempt to lure male bees into their flowers by mimicking the appearance of a female is less about sharing resources and more about taking advantage. It’s true that the bee gets a scent from the flowers which attracts female bees, but other natural perfumes can (and in the past have) been able to achieve the same with less effort for the male bee. Evidence suggests that Euglossini bees originally relied more on fungi to add their scent before the Orchid developed to take advantage of their need.

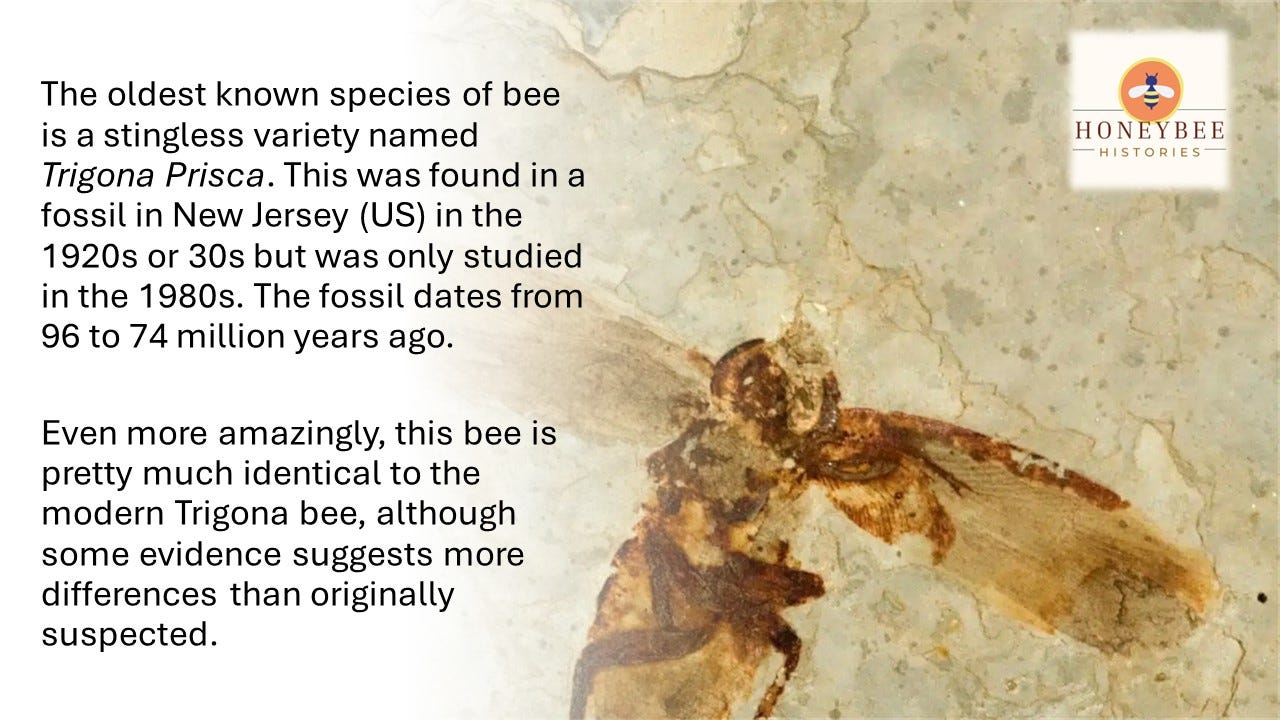

Fact #2: Trigona Prisca

In 2000, Michael S. Engel wrote an article offering a new interpretation of the oldest fossil bee, the Trigona Prisca. He mentioned that the fossil was found in the 1920s or 30s by Alfred C. Hawkins. When Engel and his colleagues studied the amber fossil in the 1980s, they found that it pushed the earliest known date for bees back from approximately 45 million years ago (Middle Eocene) to approximately 65 million years ago (Early Eocene.

The Eocene epoch is the second of the Paleogene Period in the Cenozoic Era. Essentially it spans about 56 to 33.9 million years ago.

The dating took many some 20 years to establish with various alternative dates suggested and then discarded. More than this though, the fossil proved that bees were already fairly diversified by this date, suggesting an even earlier date for their original emergence.

Trigona Prisca is a sub-species of stingless bee, which probably constructed its nests in pre-existing cavities. Although it has traditionally been placed into the Trigona family, Engel suggests that there could be a case for transferring it into a new genus entirely. He admits that it is very similar to modern Trigona but has differing hairs across its body and a slightly different body shape.

See: Michael S. Engel, ‘A New Interpretation of the Oldest Fossil Bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae)’, American Museum Novitates, 3296 (April 2000). Online

Fact #3: Ra the sun god and Ancient Egyptian Bees

In an essay that I wrote back in January 2024, I described how the First Dynasty of Ancient Egypt used the bee as part of its symbol of kingship. The sun god, Re (or Ra) was a key component of this belief that bees were in some way sacred and kingly. The association of bees with Re in particular, was first identified by Henry Salt, Britain’s first consul-general to Egypt. In 1816 he found a papyrus that told the story of how the sun god Re made the bees:

“The god Re wept and the tears from his eyes fell on the ground and turned into a bee. The bee made (his honeycomb) and busied himself with the flowers of every plant; and so wax was made and also honey out of the tears of Re.”

This association makes more sense when we consider Re’s role as the sun god. Egyptians believed that he was the great creator – rising each day to bring life and dying at the end of each day to bring about renewal for the next. In this context, the suggestion that Re’s tears created the bee shows recognition that bees only operate during the daytime and are renewed through swarming behaviour. The ancient Egyptians were obviously able to observe how wild colonies would appear and disappear and renew themselves as swarms separated from old colonies and made new ones, thus mirroring Re’s daily rise and fall.

Fact #4: The Red-tailed Bumblebee

The Red-Tailed Bumblebee (Bombus lapidaries) is in the subgenus Melanobombus and can be found throughout Central Europe. Their nests contain only a few hundred bees at most and are not considered to be complex societies. Nonetheless, they can travel long distances to forage for pollen and nectar.

First recorded by Albany Hancock (1806-1873), the red-tailed Bumblebee was one of many species of bees that he described in his notebooks. Hancock was born in Newcastle and would regularly explore his local region to seek out insects. He was an enthusiastic amateur naturalist from childhood but only started to ‘professionalise’ in his 30s. Rapidly he became one of the foremost naturalists of his day and wrote around 70 publications during his lifetime. Many of the specimens that Hancock collected can now be found in the Hancock Museum in Newcastle upon Tyne.