Facts about the History of Bees 2024 Part 3

Genetics - Thomas Hill - Leaf-Cutter Bees - Mason Bees

While Honeybees are our focus, other species of bees are just as important to the ecology of our world and deserve our attention. Therefore, every year for #WorldBeeDay, I create 24 tweets (one per hour) to share interesting historical facts about the various species of bees.

In this week’s Honeybee Histories newsletter, I’m presenting four facts with some additional details and a short video. I hope you enjoy them.

Fact One

The suggestion that honeybees originate from Asia rather than Africa, as has generally been thought is quite a startling conclusion. As with any scientific discovery, the scientists hedge their conclusions as a probability, rather than certainty, but they do offer some convincing evidence. Their main claim is that honeybees appear to derive from cavity-nesting bees that arrived from Asia around 300,000 years ago. As one of the authors argue:

“The evolutionary tree we constructed from genome sequences does not support an origin in Africa, this gives us new insight into how honeybees spread and became adapted to habitats across the world” (Matthew Webster).

Indeed, in the article itself the authors note that some hypotheses have placed the origin in the Middle East, based on limited analysis of genetic and morphometric markers. Others have maintainted the traditional view that they originated in Africa. Indeed, a study from 2006 concluded that an African orgin was most likely, claiming that the alternative view that A. mellifera (the European Honeybee) and A. cerana, splitting in Asia, and expanding into Europe and Africa, does not bare out in their analysis.

More research is most likely needed and we might never be entirely certain of honeybee origins. However, the Uppsala study certainly takes us nearer.

The main finding in the Uppsala study though, is that honeybees have a wide genetic diversity within them. This suggests that they interbreed openly and with bees from different parts of the world. This shouldn’t be too surprising a conclusion. In part, honeybees genetic diversity is due to the honeybees own instincts, but it is also because of us. We routinely transport bees from other countries to improve stocks in the eternal quest to manage calm, resilient, and hard working colonies.

Sources

Wallberg, A., et al., ‘A worldwide survey of genome sequence variation provides insight into the evolutionary history of the honeybee Apis mellifera’, Nature Genetics, 46:10, (2014), pp. 1081-1089.

Whitfield, C.W., et al., ‘Thrice out of Africa: ancient and recent expansions of the honey bee, Apis mellifera’, Science, 314 (2006), pp. 642-645.

Fact Two

I have written about Thomas Hill’s A Profitable Instruction of the perfect ordering of Bees a fair bit on Honeybee Histories. Indeed, the subject of Hill’s reliance on Georgius Pictorius’ Pantapolion has been covered in some detail in the sixth part of that ad-hoc series: Did Thomas Hill plagiarise the first beekeeping manual printed in English? I also discuss there, Charles Butler’s accusation of plagiarism against Hill. What I didn’t talk too much about in that essay was Georgius Pictorius himself. This, therefore, seems like a good opportunity to rectify that missing detail.

Georgius Pictorius (1500-1569) was a German physician and author who focused most of his writings on the occult, rather than natural philosophy, or animal husbandry. However, in reality he wrote on a variety of subjects including philology, medicine, health, botany, and zoology. In part this is similar to Thomas Hill, who also wrote on a variety of scientific and semi-scientific topics.

We know that Pictorius was born to the butcher, Michael Painter, in Villingen (Black Forest) in 1500. At this time Villingen was under Austrian lordship and remained Catholic during the Reformation. We know that he studied the liberal arts in Freiburg and that eventually (around 1529) he took over the management of the Freiburg grammar school which gave him the money and the opportunity to study medicine, graduating with a doctorate in 1535. For the next few years Pictorius worked as a doctor in the vicinity of Freiburg, soon becoming involved with the government, which gave him the opportunity to write scholarly works on a variety of subjects.

In total Pictorius wrote more than forty printed works on a variety of subjects, although it was his work on magic and the occult that proved to be his most popular works. On this subject, Pictorius supported the burning of suspected witches. He also argued that witches were also demons and that they were prolific in producing ‘apelike’ monsters.

Very little of this seems to influence the treatise on beekeeping. I’m currently unsure why Pictorius would have chosen this particular topic for study, however, it was not far from his other interests in medicine, botany, and zoology. Perhaps he chose bees as a specific case study. Whatever his reasons, his publication gave Thomas Hill a detailed basis for writing his own beekeeping manual in English, albeit one which was half taken entirely from Pictorius’ work.

Fact Three

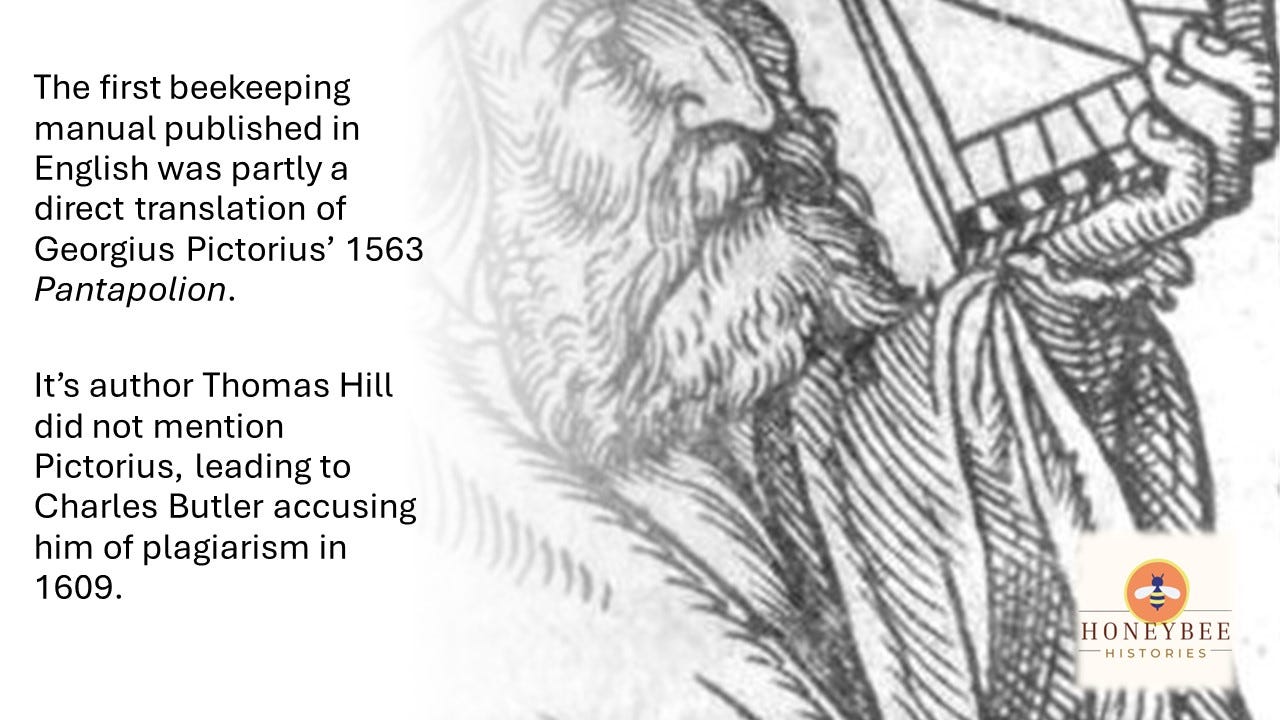

The Guardian article was republished on Sunday 14 August, as a reproduction of the original published 15 August 1916 in the Manchester Guardian. It describes the activity of the leafcutter bee with some interest:

“A Wilmslow correspondent has sent me the remains of a crimson geranium, for from each petal a neat semicircular portion has been removed. He watched a bee snipping the petals and bearing them away to a hole in the mortar on his house wall; he asks what the bee is and why it wanted the bits of flower.”

The author of the article, Thomas Coward, explained that the correspondent had been watching a leaf-cutter bee and that the cut bits of the leaves were to be used for building the cells in which it would lay its eggs.

“In the selected crack or tunnel the cells are placed in a long row, fitting neatly into one another; each oblong cell is formed of folds of cut leaves or petals, the insect cutely taking advantage of the insward curl of the drying vegetable tissues in the construction. The base of each cell is convex, in it an egg is placed and a supply of food, and then a concave door, usually formed of several layers of leaf, wonderfully rounded and out to size, closes the cell until the perfect bee is ready to push its way out.”

An interesting point suggested by Coward is that some leaf-cutters ‘show aesthetic taste, selecting red or yellow petals’. Is there any truth to this claim or just imaginative fancy? Coward admits that most simply take from the leaves of garden roses, so the inclusion of petals might just be accidental.

Indeed, there is some evidence to support the claim. In 1995, Marjorie Horne argued that:

‘many species are selective foragers and consistently remove cuttings from only a few plant species’

and that:

‘although strong preference responses are often collectively demonstrated by either a megachilid population of species, variations in preference among individuals may still occur. These variations can produce a collectively lowered preference response for many plant species and may become more pronounced when preferred plants are not available’.

However, mostly this is limited to characteristics such as leaf size, thickness (and ease of cutting). Another study based in India suggested that leaf-cutter bees had a preference for Fabaceae flowers (peas and beans), which have evolved to protect its pollen from other bees, but appear to be more adapted for cutter bees. Perhaps, the same is true of the rose family in Europe? Certainly, many studies have observed that leaf-cutter bees have a preference for rose bushes.

There is almost certainly more to be learned on this subject (perhaps a future Honeybee Histories essay?).

Sources

Horne, M. (1995). Leaf Area and Toughness: Effects on Nesting Material Preferences of Megachile rotundata (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 88(6), 868–875. doi:10.1093/aesa/88.6.868

Pradeepa, SD., and V.V. Belavadi, ‘Floral preferences for pollen by leaf cutter bees (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae) in Bangalore, India’, Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies, 6:4 (2018), pp. 588-596.

Fact Four

Born in Ireland, Oliver Goldsmith (1728?-1774) had a life marked by financial challenges and a yearning for intellectual pursuits. He initially studied medicine, then travelled across Europe, and embarked on a literary career. His A History of the Earth and Animated Nature was written near the end of his life, at a time when he had not only become highly successful with fictional stories, poems, and plays but also with intellectual works about history and nature.

Indeed, Goldsmith had made for himself quite a distinguished reputation for fictional works such as “The Traveller” (1764) and “The Vicar of Wakefield” (1766), but was also known for non-fiction, especially his The History of England and Dr Goldsmith’s Roman History Abridged by Himself for the Use of Schools. What had initially found him fame though, was his series of fictional accounts published in the Public Ledger about a Chinese traveller in England under the title The Citizen of the World.

Goldsmith’s focus on nature was an extensive work for which he earned 100 guineas. He wrote it during a summer retirement in a farmer's cottage near Hyde. Regarding the Mason-Bee this is what he wrote:

“Mason-Bees make their cells with a sort of mortar made of earth, which they build against a wall that is exposed to the sun. The mortar, which at first is soft, soon becomes as hard as stone, and in this their eggs are laid. Each nest contains seven or eight cells, an egg in every cell, placed regularly one over the other. If the nests remain unhurt, or want but little repairs, they make use of them the year ensuing: and thus they often serve three or four years successively. From the strength of their houses, one would think these bees in perfect security; yet none are more exposed than they. A worm with very strong teeth, is often found to bore into their little fortifications, and devour their young.” (Goldsmith, 1825 ed.), vol. 1, p. 808)

Sadly, Goldsmith died at the age of 45 at the peak of his literary and intellectual work. The news of his passing was met with widespread mourning and he was remembered for his wit, warmth, and the enduring power of his writing!