Charles Butler Part 2 - Based on Observation!

In part 2 of 3 essays, we explore the contents of Charles Butler's 1609, The Feminine Monarchie, including what he got right and what he got wrong!

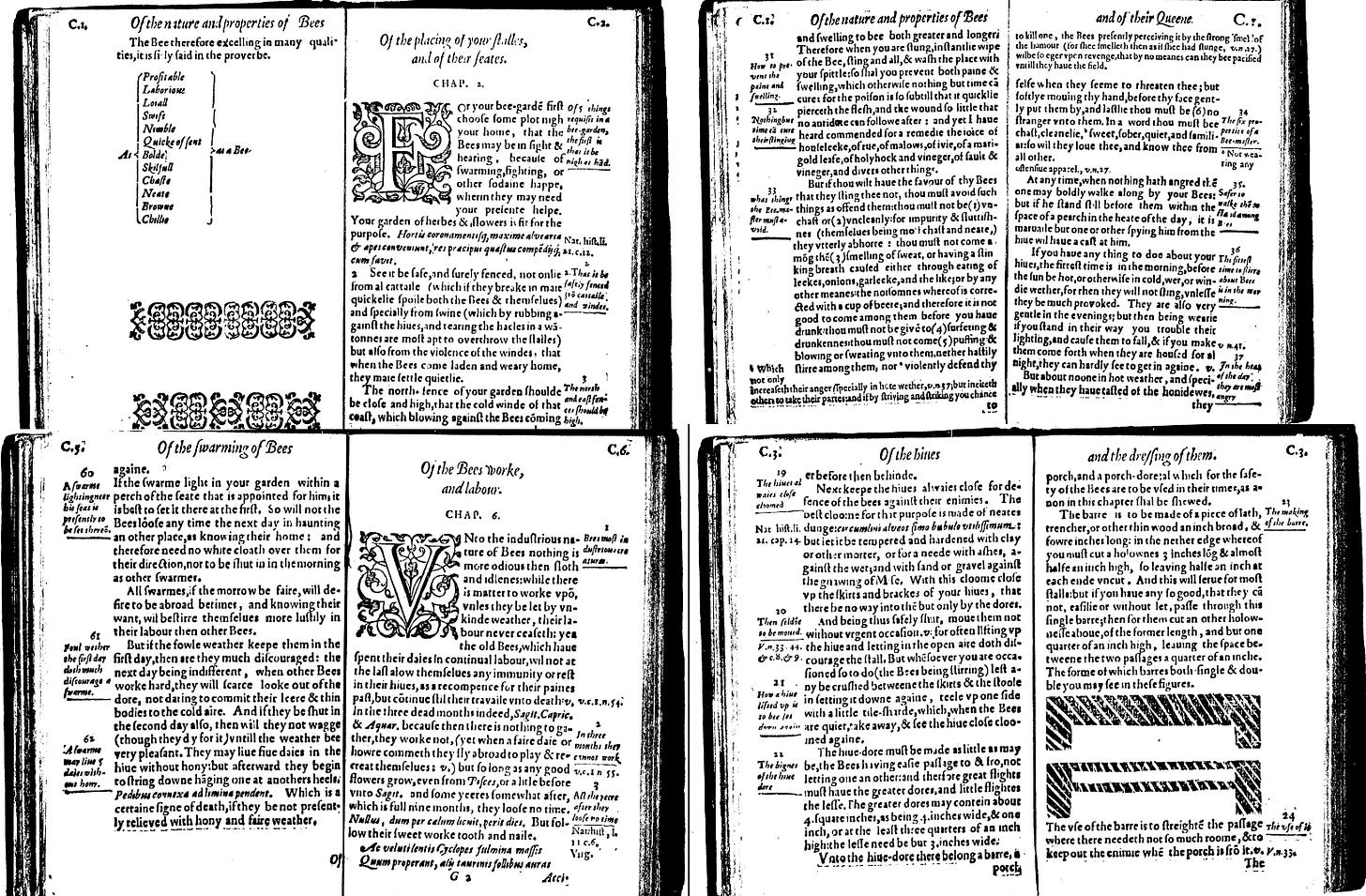

In part 1 of this short series on Charles Butler, I explored some of the key themes and challenges when reading The Feminine Monarchie, arguing that while Butler’s work was indeed a major step forward and much more ‘scientific’ than what had come before, it was also more traditional in its approach than is often suggested.

Following that essay, I added a profile on Charles Butler himself, noting how he seemed happy to remain in a small vicarage despite his capabilities. Butler took up beekeeping not as a simple hobby but to make money, and it seems that he was successful. He also observed his bees carefully, which allowed him to write The Feminine Monarchie in 1609, and to provide an account that was more accurate and detailed than anything that had come before.

In part 2 of this series, I have decided to explore the contents of The Feminine Monarchie in more detail. This is, of course, a wide ranging topic, so I will keep my exploration to some of the key elements and to what other researchers have highlighted in their studies of Butler’s work. If you enjoy this read please do consider adding a comment or liking the post. I’d love to hear from you.

In his 1994, Great Masters of Beekeeping, Ron Brown found in Charles Butler’s work a reference to ‘scout-bees’ or ‘spies’ dancing and shaking their wings on clustered swarms. Specifically, Butler had stated:

“For when they [the swarm] are once settled, they soon send forth spies, to search out an abiding place, who if they return with good news before swarming-time is past that day, they soon rise, and are gone; otherwise, they will return with all speed, and no sooner do they touch the cone or cluster, but they begin to shake their wings as the bees do that are chilled, which their neighbours, perceiving, copy, and so does this soft shivering pass as a watch word from one to another, until it comes to the innermost bees, which causes a great hollowness in the cone.” (Owen, 2017, 63)

Brown realised that what Butler had observed here was close to the discovery made 300 years later by Karl von Frisch that the ‘scout-bees’ direct the others to an agreed upon location to establish the new colony, but that Butler had failed to make this link clear and explicit enough for others to understand this characteristic. Nonetheless, Butler should be credited for his observational skills in identifying something about bees that would not be officially confirmed for centuries. Indeed, in the same paragraph, Butler also described the waggle-dance as the means for the scout-bees to communicate their discovery of a potential new home. This again, was discovered by von Frisch but ventured here much earlier.

There are various other examples in The Feminine Monarchie, where we can identify information and detail that either confirms traditional knowledge about the honeybee or corrects misunderstandings. Butler was a good observer of the hive and his ability to describe the traditional view and then to assess its accuracy is the reason why his work has lead to him being labelled as the father of English beekeeping.

For example, in his chapter on feeding the bees, Butler mentions that Aristotle recommended that figs be fed to bees to supplement their diet when honey is sparse; Pliny recommended raisins and figs or boiled new wine, honey-water, or even ‘teased wool, made wet in sweet wine made of raisins’; and ‘some of our countrymen’, Butler added, give them ‘basil, bean flower, ground-malt, roasted pears, and apples and sweet wort’ (Owen, 2017,104). He states all of this simply to reject it all, arguing that while bees will feed on them they will still require actual honey to survive.

By making this argument, Butler separates himself from those that have come before him and popular belief in his own country and instead – through his own experiences – sides with others in his country who directly or indirectly feed the bees honey. Even here he rejects many of the methods tried (such as offering the honey on toast to the bees) and suggests the simplest possible solution; feeding them a section of honeycomb. Of course, modern beekeepers use a simple device to feed them sugar water (an expensive alternative in the seventeenth century) or fondant (which hadn’t yet been invented!).

Another example of Butler improving on the advice that had come before is the most obvious and famous claim that he made about the sex of the leader bee and, by association, the drone bee. As already argued in Part 1, Butler fails to explain his rationale for identifying the leader as a female (and thus a Queen). However, as Jonathan Woolfson (2010, 298) has argued, he did closely observe the life cycle of the hive, which most likely lead to him deducing that the leader was female and the drones, male. Such an identification would immediately impact the future study of honeybees. Richard Remnant, for example, writing nearly 30 years later took for granted that honeybees are ruled by a female (this was in his A Discourse or Historie of Bees).

What did Butler get wrong?

There are some errors in Butler’s work, most of which were likely unavoidable considering the lack of technologies such as the microscope and an as yet undeveloped process of experimentation. For instance, Butler had no idea how the bees reproduced. In this he was in good company. Bee reproduction had been a mystery for most of human existence and was only solved near the end of the eighteenth century by blind beekeeper, Francois Huber.

Butler thought that the workers lay their own eggs and that the drones fertilise them after they were laid. The truth, of course, is that the drones congregate in the air, finding virgin queens on their mating flights. Fertilisation happens outside the hive, as Huber discovered.

However, most of the errors or false-thinking had more to do with Butler following traditions and unquestioningly repeating the allusion of honeybees as a form of micro-commonwealth. Frederick R. Prete has noted how Butler used words such as ‘knowledge’, ‘loyalty’, ‘perpetual concord’, ‘amity’, ‘order’, ‘art’, and ‘diligence’ to describe the honeybee colony in terms that was more representative of human monarchy. Prete suggests that Butler somewhat ‘reorientated’ these traditional metaphoric claims, especially where it came to the correct identification of the Queen bee, but that the importance of religion and social instruction remained core to the work that he was producing.

This should not be surprising. Butler wrote in a time when it was simply accepted that studying honeybees offered a glimpse of god and that their design was gods design. This world-view influenced how he viewed honeybees, altering his appreciation and understanding. James T. Costa has suggested that Butler’s use of this metaphor ‘seems to go beyond the flattering ornamental statements often prefacing works’, therefore suggesting that Butler was serious in his analogy. Meanwhile, Adam W. Ebert has explained that ‘Butler combined religious enthusiasm, absolutist zeal, concern for the rural poor, and the desire to impart knowledge to readers both learned and unlearned’, showing that he had multiple purposes in making his study and also spoke about honeybees for those different purposes. I have to agree with these claims. Butler did not simply repeat the comparison to human monarchy as a means to clearly explain the inner workings of the honeybee colony. He did it, because he saw the virtues of monarchy whenever he made his observations and wanted to impart moral, religious, and even political arguments based on his observations and beliefs. Ebert puts this best:

“Authors like Butler drew a large measure of their enthusiasm from the feeling that the organisation and character of the hive must reveal God’s power and integrity.” (Ebert, 2009, 25).

Critical observation might have been Butler’s ‘primary tool’, as Ebert puts it, but his interpretation was not entirely neutral. His observations were still strongly coloured and aimed at various agendas.

Concluding thoughts

There is little doubt that Butler was the first truly ‘learned man’ to write on Bees in the ‘modern’ era. His immediate predecessors offered a very different product. Thomas Hill, for instance, had been skilled in Latin and translation, but he was no expert on bees. Edmund Southerne seems to have had little academic training. Nonetheless, there is a certain level of over-emphasising what is often called a certain amount of superiority in the quality of his book over the others that were written or published around the same time. Fraser, for instance, argues that Butler provided the necessary scholarly scaffolding - indices, prefaces, marginal notes including source references, and chapter and sub-chapter headings – which identifies it as a ‘real book’, by which he means a properly scholarly edition. He claims it as vastly superior to the works of Southerne and Levett, and stresses that ‘he has much more to say, and what he says is clear and correct’ (Fraser, 1958, 32).

The scholarly apparatus is certainly more complex and detailed than the other texts, but on this matter Fraser’s judgment is slightly off. Whilst it is perhaps fair to claim the work, as he does, as still the best book on skep beekeeping, the claim to its superiority in terms of quality and content risks anachronism and misunderstanding of the standards of the time. Butler’s work was a move in the right direction and did contain much more observational evidence for the claims made, but it still had one foot in the traditions of the genre and could do nothing else but contextualise honeybees as gifts from God and as examples for humans to follow.

Sources

Brown, Ron, Great Masters of Beekeeping (Northern Bee Books: West Yorkshire, 1994).

Costa, James T., ‘Scale Models? What Insect Societies Teach us about Ourselves’, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 146:2 (June 2002), pp. 170-180.

Ebert, Adam, Hive society: the popularization of science and beekeeping in the British Isles, 1609-1913, PhD Thesis, Iowa State University (2009).

Ebert, Adam, ‘Nectar for the Taking: The Popularization of Scientific Bee Culture in England, 1609-1809’, Agricultural History, 85:3 (Summer, 2011), pp. 322-343.

Fraser, H. Malcolm, History of Beekeeping in Britain (London, 1958).

Owen, John, The Feminine Monarchie or The History of Bees by Charles Butler 1623 (Northern Bee Books: Hebden Bridge, 2017).

Prete, Frederick R., ‘Can Females Rule the Hive? The Controversy over Honey Bee Gender Roles in British Beekeeping Texts of the Sixteenth-Eighteenth Centuries’, Journal of the History of Biology, 24:1 (Spring, 1991).

Woolfson, Johnathan, ‘The Renaissance of bees’, Renaissance Studies, 24:2 (2009), pp. 281-300.

Hi Matt. Great post as always.

I wrote an article about Charles Butler and natural beekeeping for BeeCraft magazine, would you like to read it?