Brother Adam and Heather Honey

How to obtain a good yield of heather honey from Dartmoor, according to Brother Adam

“There seems almost an unlimited demand for heather honey in the comb. Moreover, well-filled heather sections command the highest market price of any honey produced, either in this or any other country. Perhaps hardly any other article of food looks as attractive as heather honey in the comb. The pearly white capping’s, so peculiar to heather honey, impart to sections a most exquisite delicacy of appearance.” (Brother Adam, 1934, 2).

When I visited the British Library recently, I ordered a small booklet about heather honey by the famous Brother Adam of Buckfast Abbey. At the time it was just one of several books I borrowed about heather honey in the hope of finding enough material to write the previous essay: A history of Yorkshire Heather Honey. In the end, though, I felt that the contents of this booklet would work better as a separate entry, as the previous essay focused on the heather moors of Yorkshire, while this booklet focused on Dartmoor.

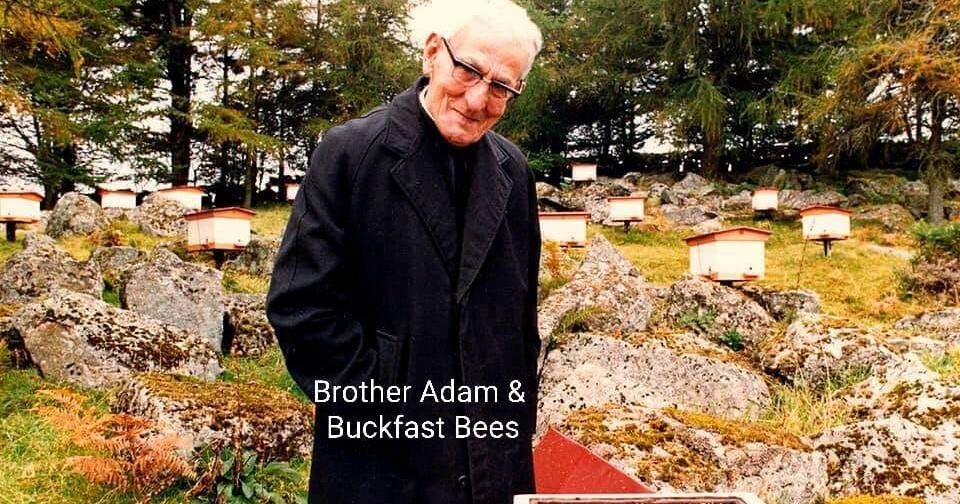

Brother Adam was a Benedictine monk born in Germany, but who spent much of his life at Buckfast Abbey in Deven, England. He made quite a name for himself for his work in beekeeping, especially his attempts to breed a better bee that would be calmer, but still highly productive. I hope to talk more about him in a future essay, but for now what interests us is the little booklet that he wrote called Some Points on Heather Honey Production, in which he used the nearby Dartmoor as his point of reference.

In this essay we shall examine this booklet but also make a few comparisons to the similar and more recent arguments that Michael Badger made in his Heather Honey: A Comprehensive Guide (2016), which focused more on Yorkshire. Badger’s book was an unexpected find. I had hoped it would contain a few introductory pages about the history of heather honey before it moved onto the more practical subject of how to manage swarms today. Instead, Badger offered a deeper history of beekeeping practices and offered some interesting antidotes and interview responses from those who worked the moors during the 20th century. It therefore works as a good comparison to Brother Adam’s earlier text.

Brother Adam originally prepared the text of the booklet entitled Some Points on Heather Honey Production for a meeting of the Newcastle and District Beekeepers Association. The meeting occurred in Newcastle on 8th December 1934 and his speech began by suggesting that the process of taking swarms to the moors was an ancient custom:

“The production of heather honey is of very ancient origin. It was known to the ancient Greeks and is referred to in old legal documents in Britain, the term “herds of bees” referring to the taking of bees to the moors.” (Brother Adam, p. 1)

I have yet to substantiate this claim, but it is not impossible that bees were taken into Dartmoor in past times. Michael Badger certainly suggests that the custom in Yorkshire dates to at least the eighteenth century (at least that is the first reference that he was able to find in print). However, he also argues that there were and are many complications and challenges arising from trying to obtain heather honey, partly due to the weather conditions, partly due to the lateness in the year (the flow occurs in late July-September), and partly due to difficulties removing the heather honey from combs. He also describes how heather moors are not entirely natural, and if left to grow entirely wild, they become less useful.

At first Brother Adam seems more optimistic, exclaiming that ‘to build up a stock for a honey-flow occurring in June or July is a simple task’. That, at least, is how he opens his argument. He later goes on to admit that it is difficult to produce heather honey economically in average seasons as the bee’s struggle to cap the honey off in their combs due to the low temperatures.

Overall, his advice is not too dissimilar to Badger, suggesting that the key is to delay the bees’ preparations for winter by artificial stimulation, doubling of colonies, or contraction of the brood-nest. Typical for Brother Adam though, is his belief that these methods will become outdated once he has found a way to breed a bee better suited to the task:

“we endeavour to solve the difficulty under consideration by strains which maintain colony-strength until late in the season, and in the unrestricted, full development of stocks’ (Brother Adam, p. 1).

Brother Adam goes into this subject in some detail, noting that Italian bees are good for clover harvests, but ‘on the heather, especially the progeny of imported queens, fail notoriously’ . He adds that Carniolan bees too do not have the right characteristics. Brother Adam suggests a cross between South French black bees and Italians to be a good choice but also highlights another option, which are bees native to the Netherlands. Dutch bees, he claims are called ‘heath bees’ on the continent as they have naturally evolved alongside moorland environments. However, Brother Adam also notes, that it is extremely difficult to get hold of true ‘heath bees’.

There is a lot of advice given in this short booklet, amongst which is a point where Brother Adam disagrees with the conceived wisdom of his day. He notes that heather honey producers often requeen their colonies in July to obtain the best results. Brother Adam admits this might be true for colonies already close to heather moors and thus a younger queen will develop the brood nest for longer than an existing queen. However, he argues, those that are to be transported act very differently:

“The jolting and general excitement caused by a journey rouses the bees to a renewed spurt of brood-rearing, to which one-year-old queens, still in their prime, respond more readily than queens only a few weeks old.” (Brother Adam, p.4).

Brother Adam also concerns himself with the placing of the hives when they are on the moor. He discusses conventional wisdom that hives should be set to face south-east but then notes that if this is done on the moor, with the hives all in a straight line, then most of the bees will end up in the hive at the end due to drifting. This is how he explains it:

“When bees return from the heather laden, they tend to enter the first hive in their line of flight. When heavily laden with nectar, they are freely admitted by any colony.” (Brother Adam, p. 7)

It is advised that hives should therefore be arranged in groups of four with the entrance of each facing a different point of the compass, and that each group should be set near a distinguishing feature such as a boulder or fern. While Brother Adam doesn’t explain why, it would seem likely, that he believes the bees to be able to use these markers to help guide them back to their hive.

Obtaining Heather Honey from Dartmoor

We are told that Bell heather blooms in mid-July and is the most common on Dartmoor, while E. cinerea heather is generally only found on low-lying moors of southern England and in Dartmoor. In explaining this, Brother Adam mentions that he was only aware of one season where there had been a heavy yield of E. cinerea (specifically 1920). He certainly considered Ling heather to be the most useful for the bees as it is most prevalent and available for them, which is exactly the same for those that Badger described in Yorkshire.

Brother Adam does add a caveat however, noting that the heather is only nectar heavy where it is grown on granite or ironstone subsoils. Where the soil is chalky or sandy, such as other southern areas, little nectar is produced for the bees to fed upon. Ironically, the ling heather is best at Dartmoor where tin mining once occurred!

Brother Adam discusses the same challenges about extracting the honey as mentioned by Badger, although he is less keen on the honey loosening machine first marketed in 1906, which Badger refers to as well. He claims that the pins sticking into the cells degrade and break and although slightly better than other means, the honey is still tricky to extract cleanly.

The booklet ends with some thoughts about how heather honey from different parts of Britain are extremely different. ‘Hardly two samples are alike’, Brother Adam muses, noting differences in colour, flavour and granulation. He ends:

“There is a decided, unmistakable difference between the true heather honey derived from the ling, and bell heather honey, or the numerous blends. Ling honey is distinguishable from other honeys by a simple test. If, on inverting a jar of liquid honey, the contents do not flow, then it certainly is heather honey.” (Brother Adam, p. 16).

Brother Adam also advises:

Make sure all comb is already drawn out before taking them to the moor, as bees at this season are extremely reluctant to do that work.

Use shallow combs to make it easier for the bees to fill them up.

Between June 20th and July 10th is when the eggs are laid by the queen which will be used for the heather crop in mid-August to 10th September. The beekeeper should only bring colonies where the breeding during that period is strong. And uninterrupted.

The hive type chosen should be large enough to accommodate a strong colony and honey supply storage, well-ventilated and secure, of a good size and shape to fit closely together with similar hives on a loading truck, provide adequate protection against fluctuations in temperature.

Drifting is a big problem on the moor (the process in which bees drift from their hive into another one). Brother Adam suggests that hives in a line on the moor will tend to end up with all the bees in the hive at the end!

Erect artificial windbreaks to protect the hives from the wind.

Placing the hives at the higher levels of Dartmoor tends to produce better quality yields than in lower areas.

During winter, colonies used for the heather flow should receive extra fed of sugar and water, as the stores are not as good for winter storage as other honey types.

Some additional notes

The edition I viewed in the British Library was a 1990 reprint of a 1934 publication. According to the front pages there were only 50 copies produced (plus the one for the British Library which remains unnumbered). It was printed by Ian S. Copinger and was a facsimile copy of the original.

The text was written as extracts from the meeting of the Newcastle and District Beekeepers Association, held in Newcastle on December 8th, 1934.

Sources

Brother Adam of Buckfastleigh, Some Points on Heather Honey Production (Durham, 1934. This edition 1990).

Badger, Michael, Heather Honey: A Comprehensive Guide (BeeCraft: York, 2016).